The presentation on React + WordPress that Gregory Cornelius and I gave at WordCamp US earlier this month is available online at WordPress.tv. Check it out if you are interested in some of the whys of Calypso or how React could work with WordPress in general.

A story about WordPress, JavaScript, and open source.

About eighteen months ago my team at Automattic set upon building an extravagant experiment for the WordPress.com interface. It was to become the most important, demanding, and rewarding project I’ve worked on at Automattic. Two weeks ago, we were finally able to unveil it to the world, and open sourced the project.

A modest beginning. Calypso 1 started as an idealized experiment, toying with the idea of what the WordPress UI could be if it was built today, entirely in JavaScript, and communicated with data only via an API. Yet, in the early days, no one really knew what it might become — if something at all —, and whether these pretentious goals would translate into a tangible thing that actually worked. Would it be possible to make such a technological leap from the current WordPress interface while retaining the solidity that was honed through years and made WordPress power a staggering 25% of the web? Would it be possible to overcome the legacy that an ageing paradigm of web rendering imposed on the evolution of the user experience but retain and foster its spirit? Given the steep learning curve such a shift would entail for everyone involved, it was also a lingering question whether we’d make it through, and if other developers would come on board to help build it.

This wasn’t the first try in this direction, either. Our previous efforts to push forward the WordPress.com user interface had yet inevitably faced the fact that the constraints and coupling of the existing codebase was too strong to overcome. Attempting to build a single page application in this landscape ended up as a convoluted attempt, with duplicated state and an awkward reliance on functionality that was not built with the considerations of a pure client application in mind. More importantly, the result was slow, hard to work with, and hard to extend. However, the emergence of the REST API around this period, which allowed a clear separation in responsibilities between the server and the client application, started to show a viable way in which a huge project like WordPress, with years of experience and legacy, could look at fully embracing modern client technologies (and with it faster iterative processes for polishing its user experience) but without dropping the solidity and permanence that had made it power such a large part of the web. In other words, an evolution of WordPress as a platform dictated by the divergence of its client application(s) and server services.

Not a framework. Even though we tried many of them, we avoided using “frameworks” to build Calypso because we appreciated the existence of single-purpose libraries that focused on one problem and solved it elegantly. Among many other modules, all pieced together via webpack, we used the small page.js router, custom data modules in raw JavaScript emitting single change events, wpcom.js as a an API connector, and React for the view rendering. The philosophies that came with React were also very appealing to us — a declarative view layer, the notion of UI as the predictable reflection of state, the importance of one-way data flows, and composition.

The fact that the client was now completely separate from the rest of the codebase would force us — and other engineers — to interact with data purely through the REST API, forcing our application to be designed without “inside knowledge”, while at the same time propelling the API itself to mature alongside the needs of a real and complex application. This decoupling naturally paved the way to fully embrace JavaScript for the entire client, no longer tied to the rendering procedures of all our legacy code, and still leveraging the backend reliability of core WordPress. Around the middle of 2014 we had a lean, modular scaffolding, composed of different JavaScript libraries running happily on our local machines (another aspect that significantly improved the developer experience) while authenticated with WordPress.com.

A need for speed. Among all the initial obstacles, there was one main reason that kept us going. How significantly faster the experience was shaping up to be. As the foundation matured, we also started glimpsing the possibilities of crafting interesting solutions that would have been close to insurmountable before, thanks to the benefits of reusable composition and a strong core. During the second half of 2014 we rapidly built the foundation of the application, honed a new — for Automattic — development process, worked on on-boarding other developers, and finalised a strong design language. By end of the year we had somewhat timidly launched a small fraction of it, the first few areas powered by Calypso in WordPress.com, and quietly celebrated the milestone. This served as an internal proof of concept and to test the reliability of the API running for millions of pageviews. But the work was just starting.

The following year had the aggressive goal of converting most of WP Admin, the default WordPress administration interface, to this new pristine greek figure that was starting to stretch its legs. At this time, some of the core principles that were guiding us, together with examples of reactivity and composition, served as indicators that this was a direction worth continuing. The success of React in the JavaScript community, a technology we had adopted very early on, was also a good sign for the direction we had settled. But more importantly, seeing the enthusiasm of other developers at Automattic was invigorating.

There’s no “I” in team. With the certainty given by the technical success of the initial launch, the novelty of such a pure JavaScript application interfacing with the behemoth that’s WordPress, and a fresh look at a cohesive UI, contributors within Automattic rapidly grew — soon covering most of the development teams. It became a huge collective effort to rebuild an administration interface that had been refined through many years and hundreds of contributors, but one that was starting to touch the walls of its inherent limits. The spirit of “I’ll never stop learning” within Automattic was never truer than in these decisive months. We were constructing a complex interface from scratch, with the cumulated experience of years but still entirely novel, and we needed to come together to execute such a difficult task. Even more, it was larger than just a rebuilding, it also supposed some significant advancements — specially around site management since Calypso was from the very start, and at its core, a multi-site endeavour.

I personally admire how strong the sense of shared ownership started to become, with teams crossing their artificial boundaries to help others, fleshing out and refining a singular experience. The engineering usability of Calypso grew significantly as the collective efforts shaped a sizeable library of components, utilities, solutions, expertise, and willingness to help. Diving deep into JavaScript was pushing our engineering literacy forward. None of us would have thought two years ago that we would be writing ECMAScript 2015 in WordPress.

Some fuel for Jetpack. Another aspect of Calypso that was demanding from the very start was that it had to be a client that treated self-hosted sites via Jetpack on an equal footing with WordPress.com sites. The goal was to let you completely manage your site regardless of where you were hosting it. This required laborious focus on both the design and engineering, syncing with Jetpack releases to power our increasing API demands. It makes me really glad that I’m writing this on the new editor in Calypso, syncing to my Jetpack site thanks to all this great effort.

Speaking of which, a test of fire for the foundation we had built came earlier this year, around March, when we had to build this new WordPress editor to go with Calypso. We were able to accomplish such an intimidating task in a very short amount of time by strong collaboration among teams, and by leveraging everything we had built so far in Calypso to speed up the engineering and design process. The new editor was announced just about a month ago. We were able to introduce a couple of cool features outside of the initial roadmap thanks to this reusability and strong codebase. (I’m personally fond of the drafts panel that allows quick switching between your working drafts from the editor itself, something that wasn’t in the original scope.)

This was a huge bet, incredibly risky, and difficult to execute, but it paid off. Like any disruption it is uncomfortable, and I’m sure will be controversial in some circles. What the team has accomplished in such a short time is amazing, and I’m incredibly proud of everyone who has contributed and will contribute in the future. This is the most exciting project I’ve been involved with in my career.

I’m glad I was able to be part of this project from the very start as a member of the Calypso core team. It’s even more exciting to see all of this released to the open world, without reservation, with the spirit of putting a piece of human craft out there — for people to look at, learn from, contribute to, and make their own.

Notes:

- Ultimately a project with about 26000 commits from around 100 people at the time we opened sourced it. See Andy Peatling’s recount of the journey. ↩

This week was the official premiere of the film Tan frágil como un segundo in Montevideo, directed by my brother Santiago. He wrote the script with Belén (who is also an actress in the film), and my other brother Javier did the photography. I worked on the editing and created these two posters for the occasion:

Such a process is always long and somewhat arduous, specially with little financing, so cheers to the whole team for getting to the closing line with the film.

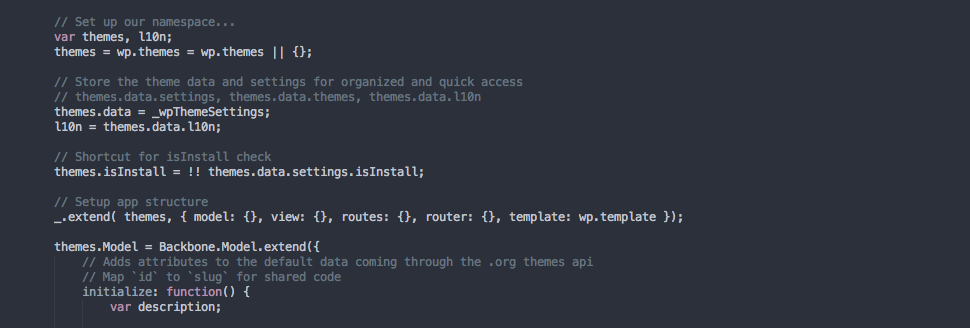

For the past couple releases of WordPress I had the privilege of working on revamping the admin theme screens, probably my biggest core contribution since developing Twenty Eleven. Working on the WordPress.com theme showcase was one of the first side projects I did at Automattic, when we were just Lance, Ian and me on the Theme Team; and I’ve worked on the many iterations since then, so I’m glad I could bring part of that knowledge to help improve the core theme screens.

The project was initially called THX38 and started as a plugin during the 3.8 release cycle. After some user tests we settled on a complete revamp of the experience, using client side technologies to make it faster and more responsive. The design removed most of the text in the screen, allowing people to focus primarily on the theme screenshots. (I’m personally fond of the arrow navigation system that lets you browse themes casually with the keyboard — maybe coffee cup in the other hand. It’s a somewhat relaxing way of looking at themes.)

It uses Backbone.js to power the client side code, something many parts of the WordPress administration panels are starting to leverage. It’s a good bridge between the robustness of the current server side codebase and more dynamic technologies to help achieve better user experiences on the client — things like searching for an installed theme is instant. We managed to get this in very close to the release deadline. Another positive result is we ended up with leaner code than before, something that would help with future improvements.

For 3.9 (just released, go grab it or upgrade!) I worked on using the same architecture and UX to power the install-themes screen, which wasn’t touched in 3.8. This meant interacting with the .org API for querying themes. Again, this made it just in time. The end result is a faster and image focused browsing experience, that also paves the way for future iterations in the versions to come. That’s something I really like — we’ve now had two subsequent releases improving core aspects of the theme experience. This agile process aligns with the momentum that core WordPress development has been gaining since the last few releases, with rapid cycles during the year, and we are looking at even more improvements around multiple screenshots, filtering system, etc. We now have a solid base for it.

Thanks to everyone that helped getting this out there, during every milestone we passed — and my special gratitude to Shaun, Andrew and Gregory.

Forest in Keswick

Taken during a visit to the town of my colleague and friend Jack Lenox, in Cumbria.

It seems to happen very often these days, that the textual editorials that accompany an art exhibition give the impression of having been created randomly, using some sort of lorem ipsum 1 generator, distinctive perhaps to the gibberish of the art world. Sometimes, it even looks as if it’s egregiously mangling arbitrary philosophical terms, throwing ontological significance at random intervals, without any aesthetic sense — nor, sometimes, even literary — whatsoever.

It approaches frightening extremes when it just reveals its utter lazy intellectualism, that builds truth for itself and then holds it to universal value, applauding its own empty wit. Every phrase seems to be more mindful about displaying a glossary of terms than in saying something relevant about the art it’s supposed to comment on. It’s always vehemently self-aware, but in absolute denial of its ephemeral nature and vagueness. Generalities, which abound, are laid out with a pretentious sense of morality, a pretentious sense of urgency in its aesthetic irrelevance. To whom?, once should ask. Because, in turn, this means such thoughts can easily be applied to any art display; and it would make no difference at all. It would appear they are battling against the actual artwork to achieve their status, to be considered themselves works of art.

What results is almost reminiscent of a surrealist cadavre exquis composition — this time with all the veils of a truly thoughtful discourse shaped by a single mind. Let’s be clear — it’s building connections to a work just because it’s physically connected to the art pieces it’s supposed to refer to, and because the reader is vehemently interested in making those connections work while nodding at the pace of its ridicule. All the correlation is drawn by the fact it’s in the same spatial context. Remove it from that context and it becomes a generic mix, of more or less persuasive ideas, but with no particular coherence. Move the walls of text from one exhibition to the other, and you would be hard pressed to spot any mismatch — so generic that they are not saying anything at all.